By Madut Ayokdit

In every functioning democracy, the strength of leadership is anchored in respect for institutional order and the clearly defined boundaries of delegated authority. These principles are not merely bureaucratic formalities; they are the bedrock upon which political stability, public trust, and national progress are built. When they are disregarded, whether through ambition, misjudgment, or a deliberate attempt to consolidate power, the consequences are often swift and destabilizing. This is the essence of what Ateny Wek Ateny astutely highlighted in his recent analysis concerning the growing tension between President Salva Kiir and Vice President Dr. Benjamin Bol Mel.

Dr. Bol Mel’s situation is not just a political miscalculation; it is a constitutional cautionary tale. It illustrates how unchecked ambition, when left unchallenged, can erode the very trust upon which governance is built. Once regarded as one of President Kiir’s most loyal allies, Bol Mel now appears to have conflated delegated power with personal entitlement, a fundamental misreading of the constitutional framework that governs executive authority. In governance, power that is delegated is never power transferred; it is a conditional trust, to be exercised with humility and restraint, not wielded as an instrument of dominance or self-promotion

Rather than anchoring his efforts within the economic cluster he was appointed to lead, a portfolio that demands urgent attention, strategic innovation, and disciplined execution, Dr. Bol Mel ventured into domains far beyond his constitutional remit. This is not merely a bureaucratic overstep; it is a breach of the constitutional compact that defines the roles and responsibilities of public office. South Sudan, still navigating the fragile terrain of post-conflict reconstruction, can not afford parallel centres of authority masquerading as initiative. The nation needs coherence, not centrifugal ambition. It needs unity of command, not a fragmented executive.

The Vice President’s actions raise serious questions about the limits of delegated authority and the dangers of institutional encroachment. History is replete with cautionary tales of deputies who mistook proximity to power for possession of it. From ancient courts to modern republics, the lesson remains the same: when subordinates begin to operate as co-sovereigns, the system recoils. Their downfall is often swift, not because of political vendettas, but because systems, especially fragile ones , instinctively reject internal disorder. President Kiir’s move to reassert executive boundaries is not an act of political insecurity but a necessary recalibration to preserve the integrity of the state and reaffirm the supremacy of constitutional order.

Dr. Bol Mel’s past contributions to economic policy may be acknowledged, but no achievement. However, laudable can justify the transgression of trust or the distortion of constitutional roles. Achievements must be weighed against the broader imperative of institutional discipline. The notion that performance in one domain grants license to operate in another is not only flawed it is dangerous. It undermines the principle of separation of powers and opens the door to personalized governance, where loyalty is rewarded with latitude, and competence becomes a justification for constitutional breach.

As the Dinka proverb aptly states, “there cannot be two bulls in one kraal.” This is not just cultural wisdom; it is political truth. Effective leadership demands clarity of roles, not competition for dominance. It requires a disciplined understanding of one’s mandate and a respect for the boundaries that define it. When those boundaries are blurred, the result is not synergy but sabotage.

At this pivotal juncture, South Sudan requires a leadership ethos rooted in discipline, not disruption; in unity, not rivalry. The President’s actions should serve as a clarion call to all public officials: leadership is not a ladder to personal aggrandizement, but a solemn trust one that must be exercised within the bounds of law, and always in service of the people. The preservation of institutional integrity is not a matter of political convenience but a prerequisite for national stability and progress.

Moreover, this episode should prompt a broader national conversation about the nature of delegated authority, the role of vice presidents, and the mechanisms by which constitutional boundaries are enforced. It is not enough to react to overreach; there must be proactive safeguards that prevent it. South Sudan’s political institutions must evolve to ensure that loyalty does not become a substitute for legality and that ambition is tempered by accountability.

In the end, the lesson is clear: power must be exercised with precision, not presumption. Authority must be respected, not reinterpreted. Leadership must be grounded in service, not self-interest. Only then can South Sudan move forward not as a collection of competing egos but as a unified nation committed to the rule of law and the promise of peace.

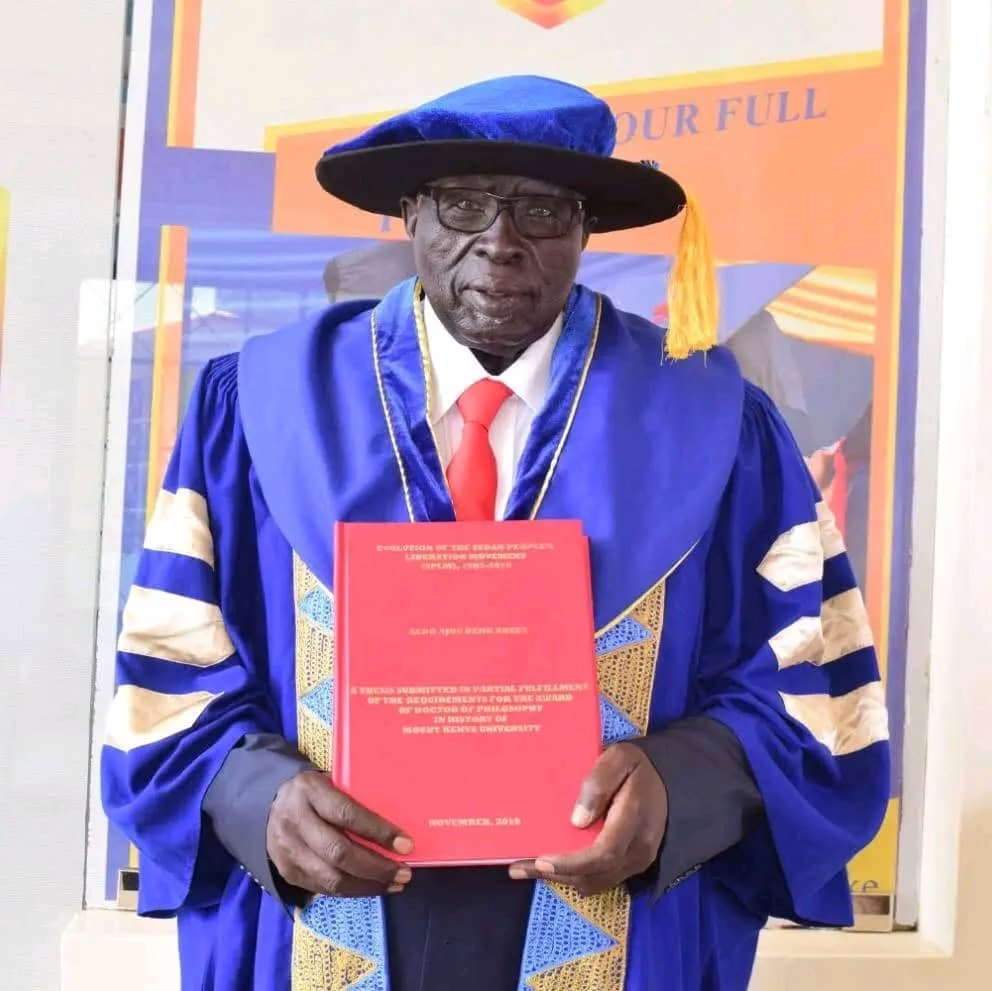

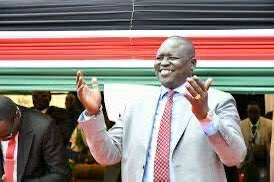

DR. Bol Mel photo taken by Thejubamirror News

DR. Bol Mel photo taken by Thejubamirror News